Rizwan Virk on The Simulation Hypothesis

Chapter Six: THE SIMULATION POINT, ANCESTOR SIMULATIONS, AND BEYOND

At some point after completing the previous stages, a civilization should have reached the simulation point—the point at which it can create simulations that are virtually indistinguishable from a base physical reality. The Great Simulation is a video game that is so real because it is based on incredibly sophisticated models and rendering techniques that are beamed directly into the mind of the players, and the actions of artificially generated players are indistinguishable from those of “real” biological players.

In this chapter, we explore what the simulation point looks like and then revisit some important implications of a civilization reaching this point. In doing so, we’ll look in detail at philosopher Nick Bostrom’s simulation argument, which helped launch a series of debates online about whether we are living inside a simulation.

We’ll delve into details of ancestor simulations, the term Bostrom uses for such simulations, and what it means for the civilizations that are able to produce them in base reality, another term attributed to Bostrom. Bostrom’s surprising conclusion is that if any society ever makes it to the simulation point, then it is more likely that we (all of us) are already inside a simulation!

STAGE 11: REACHING THE SIMULATION POINT

There are other various technical hurdles that would have to be overcome on the path to the simulation point that we did not call out as explicit stages, but these are mostly implementation challenges and not fundamental technology development milestones. For example, the ability to support billions of simultaneous individual players (a number that no MMORPG has been able to support thus far, but that websites and apps like Facebook do support), with significant amounts of information for each. And that’s only on one planet—given the amount of other Earth-like planets in our galaxy alone, this number of players (NPCs and PCs) might jump into the trillions. There is also the storage capability needed to keep track of this many players and the compression algorithms to allow for storage of this much data on some cloud server.

Table 1 shows some of the criteria that would define the simulation point. While the concepts of early video games and MMORPGs are quite useful, some of the key criteria are not yet met by our civilization. Nevertheless, just as a hundred years ago no one could have predicted today’s computers and video games, it is very likely that we can get to the simulation point over the next few decades and certainly within a hundred years, a small time frame by Earth standards, and a minuscule time frame by cosmic standards.

Table 1. Defining the Simulation Point: How Do We Know We Are There?

Criteria: Simulating a large game world

Notes: Procedurally generated worlds (technology partially exists, but will be improved with AI). Criteria: Photorealistic 3D rendering

Notes: Combines 3D models and textures, so improvements on existing technology. There might also be ways to generate realistic landscapes and objects using AI and skip the current 3D modeling process. Criteria: Ability to beam the signal for the simulated world into our eyes or our minds

Notes: Partially exists—light-field rendering (early stages) and mind broadcast (yet to be invented). Criteria: Ability to incorporate physical sensations (haptics) and feelings (emotions)

Notes: Some of these technologies for haptics exist, but incorporating emotions and mind interfaces does not yet. Criteria: Ability to take responses from our mind and react in the world

Notes: Partially invented (in the early stages), but long way to go. Criteria: Have capacity for very large number of online players

Notes: Scaling beyond what we can do today, but just an extension of our existing technology. Criteria: Storing data about players and characters in the simulation, but outside the rendered world

Notes: A very large amount of data, requires improvements on existing technology. Criteria: Implanted memories

Notes: Ability to change history and write to the brain, not yet invented. Criteria: NPCs

Notes: Artificial characters being simulated, partially exists, needs improvements on existing technology. Thus far, we have talked about the simulation point as a pivotal moment in time and have shown the road map to a technological civilization, like our own, that would develop video game technology to the point of being able to build the Great Simulation.

I haven’t, however, given a formal definition of this point, which I will do now:

The simulation point is a theoretical point at which a technological civilization can create virtual worlds (simulations) that are indistinguishable from physical reality (across all of our senses) and populated with virtual beings that are indistinguishable from physical beings.

I like to call the simulation point a type of technological singularity, because after this point, humanity will be different, or, as von Neumann put it, “human affairs, as we know them, could not continue.” The difference will come in the ability to experience any environment and have any kind of experience we want by having it in a virtual world and having it appear real. The AI avatars would not only pass the Metaverse Turing Test, but they would also be visually and kinesthetically indistinguishable. The AI beings within the simulation would also appear, to quote from The Thirteenth Floor again, “as real as you or me.”

WHAT ARE ANCESTOR SIMULATIONS?

In his groundbreaking 2003 paper, “Are You Living in a Computer Simulation?,” Oxford philosopher Nick Bostrom makes an argument that doesn’t have to do specifically with video games or science fiction, though he refers to each of them.

The argument that he makes refers to simulations as “ancestor simulations,” developed by civilizations that have advanced to a certain point. This point, which Bostrom calls posthuman, is analogous to, though not exactly the same as, what I am calling the simulation point. Bostrom speculates:

One thing that later generations might do with their super-powerful computers is run detailed simulations of their forebears or of people like their forebears. Because their computers would be so powerful, they could run a great many such simulations…. Then it could be the case that the vast majority of minds like ours do not belong to the original race but rather to people simulated by the advanced descendants of an original race.

Although Bostrom supports the idea that we may be inside a simulation running on some kind of advanced posthuman computer system (if it can still be called a computer system) without much interaction between the simulated beings and the real beings in base reality, he doesn’t get too far into the details of what is actually going on inside such a simulation. In his model, all (or certainly the vast supermajority) of the ancestors inside the ancestor simulations are artificial consciousness—simulated beings, or to use video game terminology, NPCs. Therefore, Bostrom’s argument is more concerned with the NPC version of the simulation hypothesis, and less with the RPG version, though as I have stated, this distinction is an axis more than a set of distinct categories: one simulation can have both. While Bostrom doesn’t rule out the possibility that a small, minor number of characters in one of the large number of ancestor simulations could also house avatars of players, that is not central to his argument. In fact, his argument relies on the number of simulated beings far outnumbering biological beings, so there cannot be a one-to-one ratio.

There is another key assumption in his paper that Bostrom devotes a whole section to: “substrate independence.” This basically means that “consciousness” can run on either a biological substrate (i.e., the brain) or a silicon substrate (i.e., a computer system) without significant difference:

The idea is that mental states can supervene on any of a broad class of physical substrates. Provided a system implements the right sort of computational structures and processes, it can be associated with conscious experiences. It is not an essential property of consciousness that it is implemented on carbon-based biological neural networks inside a cranium: silicon-based processors inside a computer could in principle do the trick as well.

This is quite an assumption, and one we will revisit, as it brings up a fundamental question about consciousness and what makes us human. For now, let’s assume, as Bostrom does in his paper, that consciousness has substrate independence.

BOSTROM’S SIMULATION ARGUMENT

Bostrom’s basic argument, which he called the “simulation argument,” if you boil it down, is that either mankind (or any such technological species) will reach the point at which it has the technology to create ancestor simulations or it will never reach the point. If any species is ever able to make it to this point, Bostrom concludes that we are vastly more likely to be inside a simulation than not.

Let’s drill down into the three possibilities that Bostrom brings up about any civilization ever making it to the simulation point (again, he uses the term posthuman):

A civilization never makes it to this point. Thus, ancestor simulations are not possible. Why wouldn’t a civilization make it to this point? It could destroy itself or it could just not develop computer technology in the ways that we are. A key reason would be that it’s not possible to develop fully realistic simulations, in which case this leg would be the most likely. Given the road to the simulation point outlined earlier, some aspects of this road are progressing rapidly, while others may take longer.

A civilization makes it to this point, but ancestor simulations are banned or not allowed. Why would a civilization ban ancestor simulations? This is an open question, though Bostrom gives a few ideas.

A civilization makes it to this point, and it creates many ancestor simulations. In my opinion, this is the most likely scenario, if it is possible, because most technologies developed by advanced civilizations end up being used, even if in limited form.

It’s important that Bostrom actually expresses these possibilities in terms of probabilities that we are in a simulation and makes the point that the probabilities must add up to 100 percent. In other words, one of these possibilities must be true. The most important probability from our point of view, though, is the one in the third leg. Let’s rephrase Bostrom’s math in terms of how probable it is we would be in a simulation:

In option one, in which no civilization reaches the simulation point, then the probability of us being in a simulation is zero (or thereabouts). Why? Because it may not be possible for anyone to create such realistic simulations. If it was possible, then at least one civilization would get there, eventually.

In option two, in which a civilization can create realistic simulations but chooses not to make any, the probability we are in a simulation is close to zero. In this case, though it’s possible to create simulations, they are not allowed, and so while a rogue sim might be created, there won’t be enough to get to the statistical argument Bostrom makes.

In option three, Bostrom flat out states that we are most likely in a simulation.

Bostrom actually coined the phrase “the simulation hypothesis” to refer only to option three—that we are most likely in a simulation. The term, which is not in the actual paper, as I mentioned in the introduction, has gone on to be used more generally for the idea of living in a Matrix-style or an AI-style simulation, and thus it has gone beyond Bostrom’s original usage.

THE SIMPLIFIED SIMULATION ARGUMENT

Bostrom’s argument has been used by key figures such as Elon Musk to state that the chance we are not in a simulation is only one in billions. Musk and many others have used what I like to call the simplified simulation argument, based on Bostrom’s logic, but without a lot of his math.

If option three is true—that a species gets to the point where its technology allows realistic ancestor simulations—then that species is likely to create many such simulations. This is an assumption, but a reasonable one.

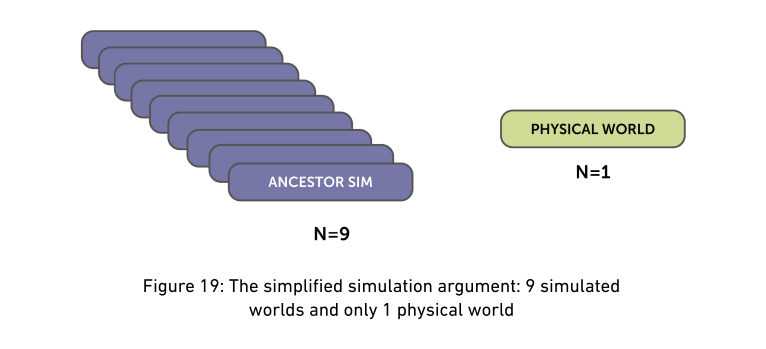

Creating a new simulation, then, is like winding up a new instance of a video game server (though admittedly this would have to be a very powerful server, from our current technology standards). If we assume there is one base reality that is creating many (hundreds, thousands, millions) ancestor simulations, then we can make a simple probability argument. In Figure 19, I show a case in which there are nine virtual worlds (ancestor sims) and only one physical world (i.e., base reality).

If you are inside a world and you cannot tell if you are in a physical world or a simulated virtual world, then what are the chances that you are in the physical world? In the diagram, I show 10 total worlds—9 ancestor sims and only 1 physical world, so the chance that you are in a simulated world is 9 out of 10, or 90 percent. Conversely, the chance that you are in base reality is 1 out of 10, or only 10 percent.

Many people object to this logic because they are overlooking the key assumption that I just mentioned, but will repeat for emphasis: You cannot tell if you are in a physical world or a virtual world. Why? Because the virtual worlds have become so advanced that everything inside them seems real.

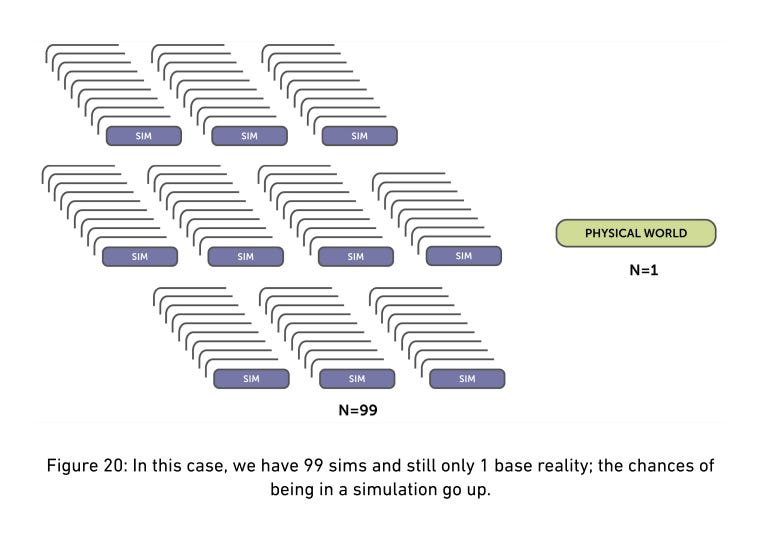

Now let’s look at Figure 20, in which we see 100 total worlds—99 ancestor simulations and still only 1 physical world. What are the chances in this scenario that you are in a simulated world? In this case, the chance is 99 out of 100, or 99 percent. The chance that you are in base reality is now 1 out of 100, or down to 1 percent.

If you continue to expand this to create a thousand, a million, or even a billion ancestor simulations, which can be done simply by adding more computing power, then the chance that you are not in a simulation becomes infinitesimally small—much smaller than 1 percent. Conversely, the chance that you are in a simulated world goes up to 99.99 percent and even higher. If you continue this logic, you can see the basis for Musk’s statement that the chance we are in base reality is only “one in billions.”

THE STATISTICAL BASIS FOR BOSTROM’S ARGUMENT

Bostrom’s actual logic wasn’t just about the number of simulated worlds. Rather, it was about the number of simulated beings (or minds) in those simulated worlds. He was trying to get the probability that you, as a being, are either a biological being in base reality or a simulated mind in a simulated reality. Bostrom states that if option three is true (that a civilization makes it to the point of creating ancestor simulations), then the number of simulated worlds will vastly outnumber the real worlds, just as we discussed in the previous section. Bostrom’s key question is, how many simulated beings will there be and how many physical beings will there be?

If we take our own civilization as an example, then the number of beings in these simulations could be in the billions or trillions because creating new beings simply requires additional computing power. Thus, for each posthuman civilization, the number of simulated beings they create will almost certainly vastly outnumber real, physical beings by a substantial margin.

Simple probability, then, tells us that because there are many more beings in simulated worlds than in the physical, real world, the chances that we are simulated beings in a simulation are very high. This relies on the key assumption that there are many more simulated beings than physical beings.

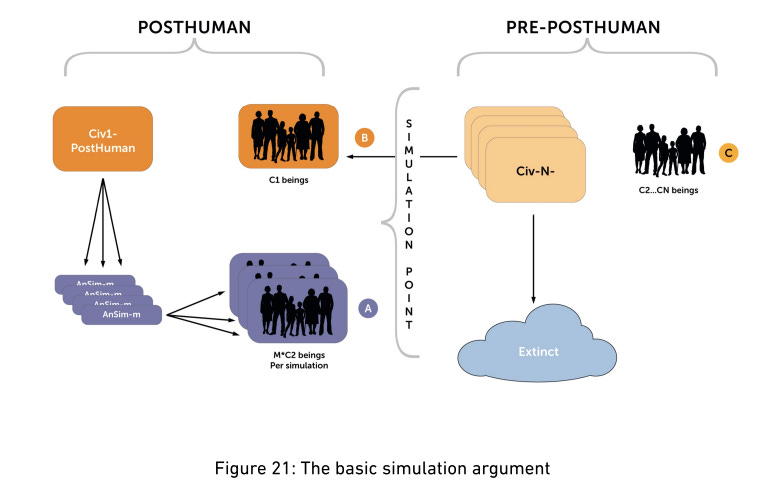

The full simulation argument can be visualized in full via Figure 21. The right side represents civilizations that haven’t made it to the posthuman stage; I would say they haven’t yet reached the simulation point. The left side represents the civilization that has made it past the simulation point.

The basic argument is that if you look at point A as the number of simulated beings and B as the number of “real” beings in that particular civilization, then A is likely to be much larger than B for a single civilization (in mathematical terms, A >> B, where “>>” means “much greater than”). This means that there are many, many more simulated beings than actual beings because it just takes computing power to spin up an entire new simulation.

The likelihood, then, that we are in a simulation is simply the ratio of simulated beings to actual beings. If A >> B, then this will be more than one (just like in Figure 19 or Figure 20)!

Bostrom uses slightly more complicated mathematics to make this same basic point: If any civilization is likely to reach the simulation point, then the number of simulated beings in all universes (simulated) vastly outnumbers the actual human beings in the “base civilization” (i.e., the “real beings” vs. the “simulated beings”).

Of course, this assumes we are only looking at the biological beings on the left side of the diagram (i.e., the civilization that has made it to the simulation point). Bostrom and his collaborator, Marcin Kulczycki, issued a patch for the simulation argument when it was pointed out that he was only looking at the real beings in the civilization that have made it to the posthuman phase. The rest of the beings in civilizations that have not yet reached the simulation point (he calls them, awkwardly, pre-posthuman) also need to be accounted for. Our current civilization (assuming we are not in a simulation) would fit into this category, as we have not yet made it to the simulation point.

These civilizations will either pass through the simulation point with the development of more sophisticated technology (as we are likely to do over the coming decades or centuries) or they will go extinct. Is there another alternative—that they survive in a pre-posthuman state for a long period of time? This depends on whether it’s a technological civilization like ours, which develops computers and video games. It’s possible some civilizations never build computers and never build video games, but it’s unlikely that a technological civilization wouldn’t have some kind of computation.

While adding in these beings makes the number of real beings larger, there is still no doubt that simulated beings can be cranked up almost infinitely very quickly, and so the basic argument still holds. In other words, A >> (B + C), though the ratio may not be as skewed as it was initially. If the number of simulated beings in all the simulations is much larger than the number of simulated beings in all the real-world civilizations, then we are still more likely inside a simulation than not!

In an interview with Larry King, physicist Neil deGrasse Tyson, while discussing Bostrom’s argument, also brings up the idea that each simulation could have beings who create sub-simulations (or simulations within simulations), so the number of simulated beings could be almost infinite. He (and others) have called this the “simulations all the way down” argument.

ARE WE SIMULATED CHARACTERS IN AN ANCESTOR SIMULATION OR CONSCIOUS PLAYERS IN A VIDEO GAME?

The most important conclusion that Bostrom makes is that we are more likely to be a simulated being in an ancestor simulation than we are likely to be a non-simulated biological being. This is assuming option three, that it is not only possible for a technological civilization to reach the simulation point, but that it does so and creates a large number of ancestor simulations.

While we can’t know the exact percentages to plug into his equations, he clearly shows that there is a nonzero percent chance that we are living in a simulation. In the FAQ of this second edition, I expand on the various probabilities that have been put forward, including my own updated estimate.

Bostrom’s conclusion is that the simulated beings are really artificially intelligent characters in simulations rather than conscious entities that have presence in the real world. This would mean that as we interact with other individuals in the world around us, if we cannot tell whether they are computer-generated beings or AI, then we can assume that whoever created the simulation was able to build powerful computers and get to the simulation point.

If we are simulated beings in a simulation, then other characters around us are already passing the Metaverse Turing Test. This means that if the Metaverse Turing Test will ever be passed, then it has probably already been passed! This assumes that it was passed in the reality “above” our simulation, while we are trying to solve it “inside our simulation” on our computers (which could, for all practical purposes, be much more simple simulated computers).

The implication under option three is that Bostrom thinks it likely that we are all simulated consciousness—in other words, that we are all NPCs. Expanding on Bostrom’s argument, as I said earlier, there is no reason why some of the characters inside these simulated worlds couldn’t be players’ avatars, even if most of the characters are NPCs. This leaves open the possibility, even under Bostrom’s simulation argument, that we are in fact not simply AI, but players in an RPG flavor of the simulation hypothesis.

WHAT IS CONSCIOUSNESS?

Whether we are dealing with the Turing Test or simulated characters, or self-aware robots or AIs like Data or HAL 9000, thus far we have been taking the idea of “digital consciousness” for granted.

We really don’t have a definition for what digital consciousness might actually be because we don’t understand what human consciousness is all about. Max Tegmark, an MIT professor and author of Life 3.0: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence, recalls that his friend, neuroscientist and brain researcher Christof Koch, was discouraged from researching consciousness by one of his mentors, Nobel laureate Francis Crick (codiscoverer of the structure of DNA). Why? Because it is a thorny issue in Western science and should be avoided.

The materialist Western science point of view seems to attribute consciousness to one of two possibilities:

Consciousness as an experience is very subjective and therefore falls outside the purview of the “physical sciences” and is ignored.

Consciousness is really the result of physical processes—that is, chemical reactions. More specifically, neural activity in the brain is responsible for consciousness, and as we are able to map out that neural activity more fully, we can easily reproduce consciousness artificially.

While No. 1 has been the perspective of many scientists over the past hundred years or so, lately, perspective No. 2 has been gaining favor with the emerging field of neuroscience.

DIGITAL CONSCIOUSNESS VS. SPIRITUAL CONSCIOUSNESS

The Eastern mystical and Western religious views of consciousness are different from those of the sciences. In the religious views, consciousness exists independent of and outside the physical body. Consciousness enters the physical body around birth and leaves it at death, according to these traditions. In some of these traditions, consciousness even leaves the body during dreams. There are now an increasing number of scientists who also hold this view, including Donald Hoffman, whose ideas we’ll explore in Chapter 14, “Skeptics and Believers: Evidence of Computation.”

Despite many materialists’ personal beliefs, we don’t know whether the spiritual or the material interpretation is closer to “reality,” and this is a debate that has been going on for many years, since well before the days of Max Planck, the grandfather of quantum physics. If consciousness exists outside the physical body, where is it? The simulation hypothesis would posit that it is stored outside the rendered world, in a world that we cannot see because we are caught inside the simulation (as avatars or as NPCs)!

In both of these cases—the materialist view (that consciousness is the result of a pattern of neurons firing) and the spiritual view (that consciousness exists outside of and is downloaded into the body)—there is one commonality:

Consciousness is really a set of information and a processing of that information (which we can call computation).

From the spiritual point of view, this information takes on various forms, ranging from a soul that is indestructible in Hinduism, to a soul that survives death and lives in eternity in heaven or hell in the Judeo-ChristianIslamic traditions, to no permanent soul at all in Buddhism, where it is seen as a “bag of karma.” In all these cases, whatever information is associated with the “player” is beamed down and linked through some mysterious process to the biological machine that is our body.

In the materialist point of view, if only we could have enough computational power to model all the connections in the physical brain, we would have a “copy” of a person at a certain point in time.

Recently, a group of researchers in Switzerland believe that they have created a scaled computer model that reproduces and acts like the brain by modeling and reproducing an individual’s neurons. They believe by modeling a rat’s brain, which might consist of “only” 10,000 neurons (with an associated 30 million neural connections), they have created a scale model that could model an entire brain within a few years. The human brain, on the other hand, is composed of networks connecting 10 12 neurons through 1015 synapses. As of the writing of this book, no one has been able to successfully model that many neural connections, but it doesn’t mean that it’s as far off as we might think.

Ray Kurzweil also makes the point, as many others have, that it’s not just consciousness that is information. The cells in your body have been replaced many times—you are literally not the same physical person you were many years ago. There must be some “information” (which Kurzweil refers to as “patterns”) that defines who you are and tells the cells how to grow. This applies not just to healthy but also to diseased cells; theoretically if all the cells are replaced, any diseased cells should just disappear on their own. This doesn’t happen because of patterns of information. Even biological entities, at their core, follow a computational structure.

Regardless of which approach you subscribe to, the materialist or the spiritualist, information seems to be a key part of consciousness. And if consciousness is information, then it can be represented digitally and could be downloaded and uploaded to “servers,” even if it is well beyond our ability to do so at the moment.

As we start to view consciousness and biological reality as a type of information, the simulation hypothesis seems more and more likely, whether you subscribe to a materialist or a spiritual worldview!

DOES SIMULATION EXPLAIN OUR WORLD?

In this part of the book, we have gone through how we might build something akin to the Matrix, showing that it is technically feasible within the next few decades or century at the most. As Bostrom’s simulation argument shows, if any civilization ever reaches this point, then it’s very possible (even likely) that we are already in a simulation.

The next two sections in this book will explore some of the reasons the simulation hypothesis actually explains many unexplained questions about our physical and spiritual worlds. This includes some of the paradoxes and unusual aspects of quantum physics, as well as the religious views expressed by Eastern mystics and Western religions.

Surprisingly, it is the religious views that are closest to the video game analogy: that our physical world is a kind of “illusion,” populated by conscious beings that exist outside the simulation. As mentioned earlier, Bostrom didn’t spend much time contemplating this possibility—his argument implicitly suggests that most, if not all, beings are simulated. Nevertheless, the idea of each of us being players watching a world that is rendered for us may be one of the most intriguing aspects of the simulation hypothesis, bridging the gap between two domains of knowledge that rarely overlap: religion and science.

In the last part of the book, we’ll wrap up by exploring additional evidence of computation, giving voice to some of the skeptics, and considering the bigger philosophical questions and implications of this hypothesis. In fact, we’ll see how the simulation hypothesis may be the one model that ties everything about our world—our science, philosophy, spirituality, and religious teachings—together in a coherent way.